I’ve had a dozen things to write lately, and all of them have been worthless, but as I was thinking how best to categorize my own financial strategy as compared to other financial strategies, I remembered some loose ideas I’ve had over time about how our financial decisions don’t operate in a vacuum. Too much bravado in any one trajectory tends to sound like cult membership. “Why is this?” I wondered.

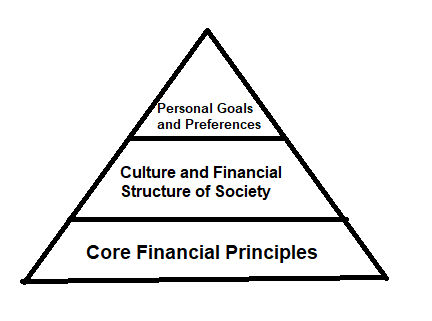

Well, that’s because there are some core levels of how these ideas are built up. At the lowest level, which I’ll call Level 1, are Core Financial Principles, which deal with operating in a world of scarcity, face-to-face with the reality of cold hard limits to the human lifespan, and the general interdependence which which humans have on each other. This level goes back to simple ecology: saving up in the Summer to survive in the Winter, cooperation among tribes, the need to carefully assess the cost of time and whether it is being used optimally for survival. Sure, you could spend your time building pumpkin launchers (sweet!), but if that’s all you dedicate your time to, you and your family will probably starve. Sorry, bro. It’s this whole idea that the universe has these fundamental laws that you simply can’t escape, but understanding them and acting accordingly has a huge impact on whether you get to look back at a life well lived or a life of destitution. Although, let’s not forget, what is often referred to as “luck” is a function of the inherent chaos and probabilities of the universe, and this has an effect on things whether you like it or not.

At Level 2, you have the specific financial structure of society. We live in a state-level society driven by electricity, especially the semiconductor. We have large economies focused on specialization, so we largely get to choose how we specialize, but each specialization has a specific economic impact based on its average wage, denominated in currency. We have access to specific investment vehicles that haven’t always existed and so are dependent upon the structure of society. Somebody in a horticultural society might not have currency and might have to use some sophisticated system of barter based on the produce of land. We even see this in enclosed communities in state-level societies, where farmers used to help each other out during harvest time, the nostalgia of which still lives with us in various holidays and celebrations in Fall (I think people actually long for a time when there was more cooperation and community). In tribal societies, wealth might be the number of children you have, the number of cows or horses or sea shells, or the number of relationships you have, the strength of tribal bonds. Whatever “wealth” looks like, it will be determined by the structures available to you based on the social/cultural landscape.

And at Level 3, you have your actual desires, goals, and preferences, laid on top of the options available to you. Sometimes you don’t have many choices, sometimes you do. Here and now, we have a whack ton of options. I work in an occupation that pays what some consider a high wage. I live strategically below my means because my economic output technically outpaces my requirements for living, as I’ve chosen to define them. I avoid home-ownership because I’m not comfortable with its risks and time requirements, so I chose an alternative approach by investing heavily in the broader stock market. Thus far, this strategy has worked really well for my goals, but I always have to remind myself that people have different goals.

At the same time, I’m starting to realize that it’s extremely difficult to find the “optimal” path, because these paths only exist when the underlying structures of society allow them. It still makes me cringe when people experience abnormally high returns on some investment or another, and then to watch them elevate that method as “optimal” because, didncha know? it’s the foundation of financial decisions? – when in fact it’s not, it simply operates on top of societal structures, which operate on fundamental principles of ecology. And you ignore those principles to your detriment because even the highest of incomes can be outspent when you fail to realize that there are limits to how long you will live, how many things you can buy, and how many years you need to work based on these decisions. Even mental real-estate is limited, as there is only so much you can productively focus on at any given time.

It is entirely possible to focus so heavily on the top-most levels that you forget the lower-levels and basically get killed in the process.

I probably have a few dozen tangents I could take from here, but I’ve had too many crap ideas lately, I’m tired.